Sitting for a spirit photographer in the hope of achieving an image depicting the ectoplasmic apparition of a deceased loved one became popular in the 1860s and 70s on both sides of the Atlantic. Spirit photographs often showed famous sitters such as the scientists Alfred Russel Wallace and William Crookes. In others, it is the spirits that are more familiar, such as Beethoven and the American President, Abraham Lincoln. These endorsements certainly added to the hype surrounding the rise of spirit photography.

Pioneering spirit photographers

In America, spirit photography began with a Boston engraver called William Mumler. In Europe, Frederick Hudson, John Beattie, FM Parkes and Reeves and Édouard Buguet were among the first. Later, their 20th-century counterparts included Robert Boursnell, Madge Donohoe, William Hope and Ada Deane.

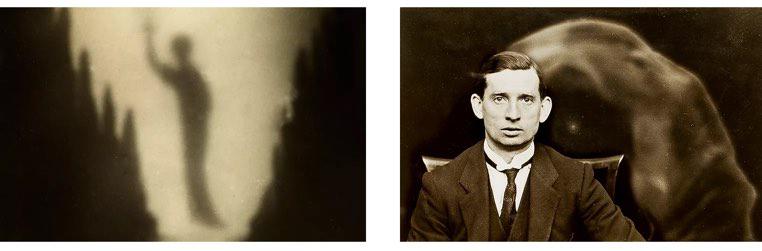

Some spirit photographers, like Hudson, invited mediums to attend in order to heighten spiritual activity. Celebrated spirit artist, Georgiana Houghton, was one such medium. She visited Hudson's studio in London over 250 times and even published a book on the subject. Early in the 20th century, psychic investigator Staveley Bulford created a series of beautiful spirit photographs in his experiments to prove a medium was not needed in the process.

Spirit photography hits headlines

Spirit photography ignited excitement among a growing number of spiritualists. The practice also attracted swathes of psychic investigators who, in their determination to detect fraudulent activity, placed the photographer under stringent testing conditions. Most spirit photographers were accused of fraud at some point in their career and, on occasion, were even convicted. Not surprisingly, the spiritualist and popular press kept a close eye on events and devoted column after column to the latest escapades of photographer and investigator.

Types of spirit photograph

For the most part, spirit photographs consisted of revealing the invisible spirits connected to a sitter during the development of the photographic plates. Rarer, was the practice of capturing spirit activity during a seance which could include floating objects, orbs of light, ectoplasmic protrusions from the orifices of the medium to full body materialisation in the case of Florrie Cook and her materialised spirit, Katie King.

Developments by Madge Donohoe in the 1920s heralded a new type of spirit photograph called the skotograph (a term coined by College member and investigator, Felicia Scatcherd). The skotograph did not even need a camera. It involved a person holding the plate to the body, normally the forehead, to transmit thoughts or messages from the spirit world. Once developed these eerie forms would appear much to the delight of the beholder.

Fabricated photography?

From the 1930s spirit photography's popularity waned due to the relentless accusations of fraud and offering images of deceased loved ones became the realm of artists such as Frank Leah and Coral Polge in their roles as spirit portrait mediums.

The College archive holds an unparalleled collection of spirit photographs from all the major practitioners mentioned above as well as many more. Its fascinating history is also well documented in the books and periodicals of the library.

Featured images: From the College Archive: Skotograph by Madge Donohoe circa 1929 and a spirit photograph by Staveley Bulford, 1921. © College of Psychic Studies.

Our Archive welcomes researchers and visitors. Contact our archivist Vivienne for more information.