Frederick John Staveley Bulford is often overlooked in the history of spirit photography. He was not a celebrated medium or a pioneering photographer, but a carpenter. However, his passion for magic and psychic investigation led him on a journey which culminated in some of the most striking spirit photographs ever achieved. The College of Psychic Studies owns many of his images - on his death, he bequeathed us his collection. Here, College Curator Vivienne Roberts shares a little about what inspired Staveley Bulford's experiments.

The Cottingley fairy photographs

Spirit photography, after its golden age in the 1870s, grew in popularity once again after the First World War. The publication in the popular Strand Magazine, December 1920, of the Cottingley fairy photographs caused a sensation and brought the phenomena to the notice of the general public. In spiritualist circles, the mediums William Hope and Ada Emma Deane were the chief exponents of this second ascendancy and their work was in high demand.

Like their predecessors half a century earlier, these protagonists were frequently accused of fraud and attracted the attention of several well-known psychical investigators. Harry Price wished to expose them as charlatans, while Sir Arthur Conan Doyle sought to prove their innocence and celebrate their accomplishments. Spiritual publications, including Light, were dominated by the conflicting results of these investigations, as well as many reports from members of the newly formed Society for the Study for Supernormal Photographs (1918-23). Spirit photography became a fiercely debated topic. Amongst this maelstrom, Staveley Bulford, then a young psychic investigator with limited knowledge of photography, was on a quest to find the truth so he joined the fray.

The rising star of Staveley Bulford

Frederick John Staveley Bulford (1885-1958) was born in Southampton. His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were all carpenters, a skill also adopted by Staveley who became a joiner at 16 and later a woodwork teacher. However, from an early age, his passion was magic. He started by entertaining his childhood friends, developed into an enthusiastic amateur, and later became a member of the Magic Circle. Staveley described its headquarters in the early days at St George's Hall, London as "the home of every conjuror of repute" and where "so-called spiritualist tricks were the chief items of interest". From here he was able to study closely the work of magical masters such as John Nevil Maskelyne and David Devant. He even adopted some of their 'spiritualist' tricks in his own performance which he entitled a Grand Magical Séance and performed under the stage name, Basil Dare.

Magic & Carpentry

Staveley's talent for conjuring and carpentry put him in good stead a few years later when World War One engulfed British life. During the day, he worked for the War Hospitals Supplies Depot teaching woodwork skills to hundreds of volunteers so they could make crutches and surgical appliances for the injured soldiers. He also helped raise funds by curating a highly successful Exhibition of War Trophies in 1918. Staveley's war effort didn't stop there - he devoted his evenings to performing conjuring tricks at YMCA huts and hospitals for wounded soldiers, of which one newspaper stated it "afforded unbounded pleasure".

Shortly after the war Staveley married Muriel Beatrice Harrison, a wealthy heiress, and their son, Staveley Ernest Bulford, was born in 1919. Fueled by the growing interest in spiritualism from a country seeking solace after the devastating losses of war Staveley returned his attention to psychic research. It was an interest which began before the war broke out when two sceptical friends invited him to witness the physical mediumship of John Taylor of Farnworth, Lancashire. They knew his capacity as a skilled conjurer meant he would be able to detect trickery, yet Staveley described Taylor as around 70 years old, kindly, and "looking not at all like the fraudulent trickster we imagined him to be".

Staveley's first séance

In his book, Man's Unknown Journey, 1943, Staveley recalls the experience of his first séance; "Imagine a very confident conjuror in the presence of his friends, in a well-lighted room, sitting on a plain wooden chair on top of a circular table. Everything in the room had been microscopically examined. The kindly old man stood by this table and slowly, slowly, the chair and the conjuror went up and up towards the ceiling, remaining in mid-air for sixty long seconds then falling swiftly back to the top of the table. Incredible!". He stated that the psychic phenomena seen that evening was "genuine beyond reach of all the technique of trickery and all the scepticism of a conjuror". It was the starting point of his lifelong interest in psychic research and belief that communication with spirits was possible.

He began to regularly attend séances and on one occasion was amazed to see what he believed was "the masterpiece of all psychic phenomena" - the materialisation of a spirit. To him this was the most definite evidence in proving the continuity of "life, consciousness, memory and individuality." Furthermore, it wasn't any old spirit, but instantly recognisable as his mother, who had died in 1908 when Staveley was just 23. At a later date, he witnessed the materialisation of his sister who had died in childhood. Staveley's belief in the existence of a spirit world was in no doubt, but he still needed to investigate how it was possible.

Capturing ectoplasm

After the war, Staveley was able to return to these investigations into materialisation. He claimed he was spiritually guided by a scientific man who had taught him that it was possible to utilise an invisible stream of vital forces emanating from the body and its aura to create ectoplasm. The ectoplasm could then be moulded by an unseen operator into any form desired and appear as a materialised form which under certain conditions could become visible. Staveley found from his experiments that by consciously controlling this ectoplasmic projection, he could also influence the outcome of the materialised form. His findings would be a psychic breakthrough as hitherto materialisation had been limited to the unconscious power of a physical medium who had no control over the materialised form.

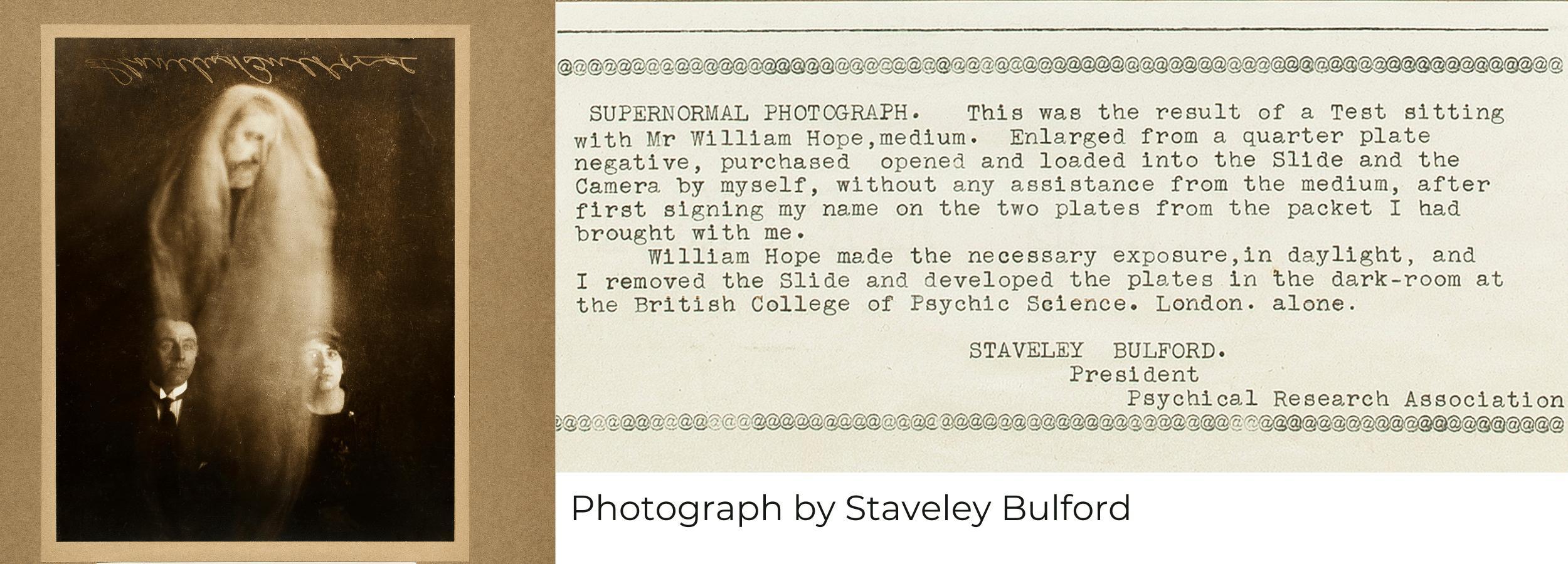

On hearing about these successful experiments a friend, Miss Evans, made the suggestion that Staveley should accompany her to an appointment with the celebrated spirit photographer William Hope, in order to test his theory of "ectoplasmic projection". Also, as a conjuror, she thought he would be well equipped to detect fraud. Staveley agreed and took with him his own marked plates which never left his sight. He even remained with Hope in the darkroom so he was fully content that no trickery had taken place.

Staveley Bulford's spirit photography

The result was a perfectly formed spirit photograph, which gave Staveley the idea for a new set of experiments. He was convinced that spirit photography, using ectoplasmic projection, could be achieved without the aid of a medium. He concluded that "granted the presence of a suitable group of people - the necessary ectoplastic material would be at hand for the production of such pictures, provided that the necessary help on the part of unseen intelligent operators were forthcoming".

On 18 March 1921, Staveley, his wife Muriel, Miss Evans and Mr Bird, a photographic expert from the RAF, met at the studio of professional photographer, Mr Scott in London. Mr Bird and Mr Scott were sceptics of spirit photography, but willing to give the experiment a fair chance and their expertise in photography was needed to counterbalance the others' lack of knowledge. The main aim was to discover if super-normal effects on the plates could be achieved without the aid of a medium. Staveley was adamant that the experiments were "not an attempt to obtain recognised human faces or similar evidences pointing to the survival of personality. The whole object was clearly one of scientific research". It was also assumed that the experiments were controlled by unseen operator in the form of Staveley's guide 'the professor'.

Experiments with ectoplasm

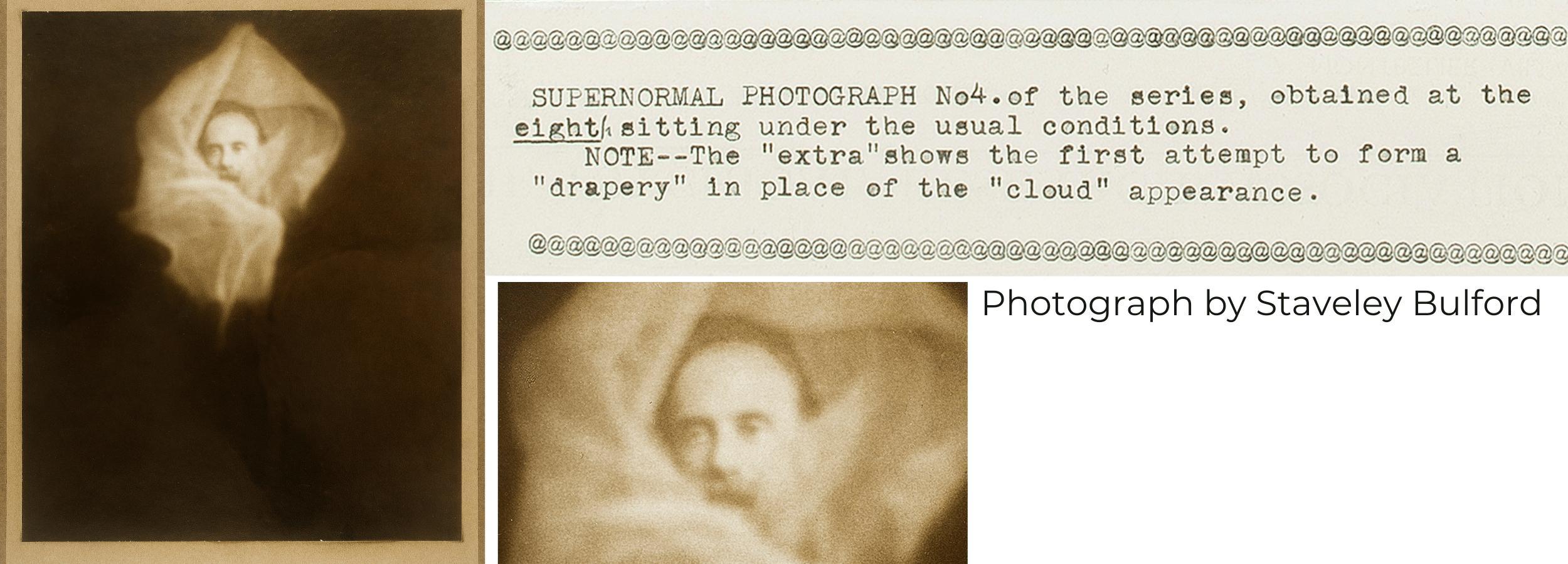

Weekly meetings took place where the sitters would be free from emotion or anticipation. The experiments were executed in full light. The lighting levels and the plates and cameras were adjusted to see what affect it had on the results. They sat in silence for ten minutes to start. Staveley concentrated on generating his stream of invisible ectoplasmic force which spirit intervention moulded into a materialised state and, although not dense enough to be seen by the eye, it contained electromagnetic properties which were used by the spirit to manipulate the photographic plates. At no time was fraud detected.

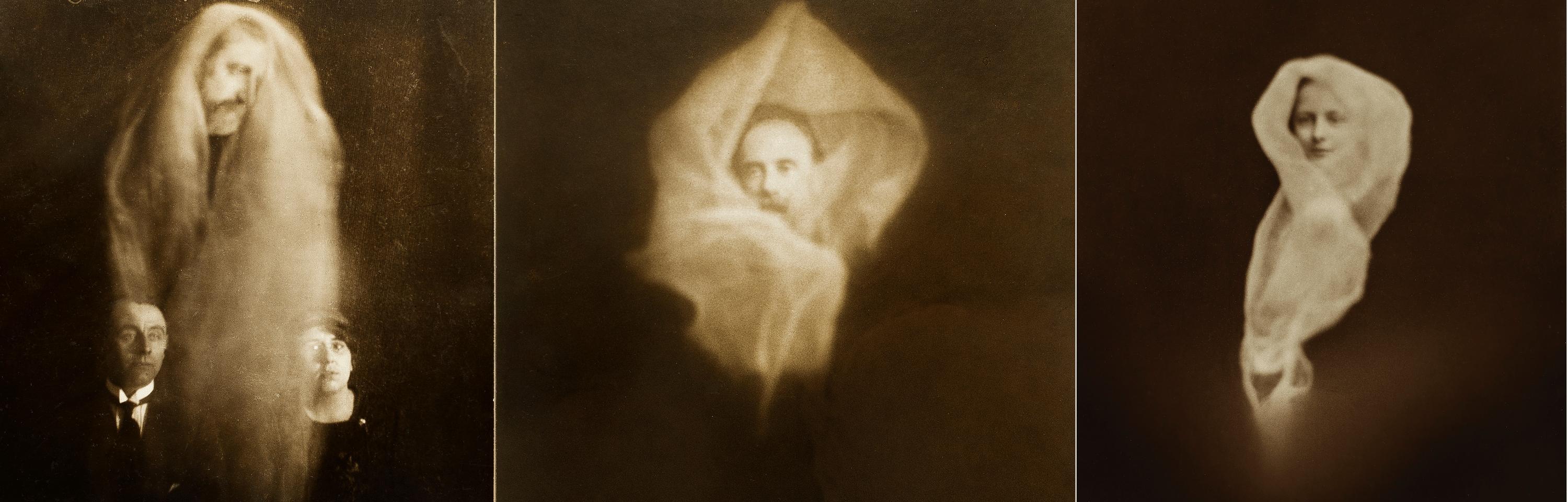

The experiments finished on 21st July 1921, and of the fifteen that took place, eleven obtained successful results. There were a total of twenty seven 'extras' in the photographs ranging from small orbs of light to results described as "remarkable for their quality of definiteness and in many cases artistic excellence." According to Staveley, it was a brilliant success which Sir Arthur Conan Doyle acknowledged in his book The History of Spiritualism in 1926 saying "Some mention should be made of the remarkable results of Mr. Staveley Bulford, a talented psychic student, who has produced most excellent genuine psychic photographs. No one can look over his scrapbook and note the gradual development of his gift from mere blotches of light to very perfect faces without being convinced of the reality of the process."

Proof of Spirit

Staveley believed that the use of mediums in spirit photography often led to accusations of fraud which overshadowed the achievements of psychic phenomena, and his experiments proved that spirit photography was achievable without the use of a medium. He was convinced that his spirit photographs, achieved under strict controls, could stand as unsullied evidence that spirit communication was possible.

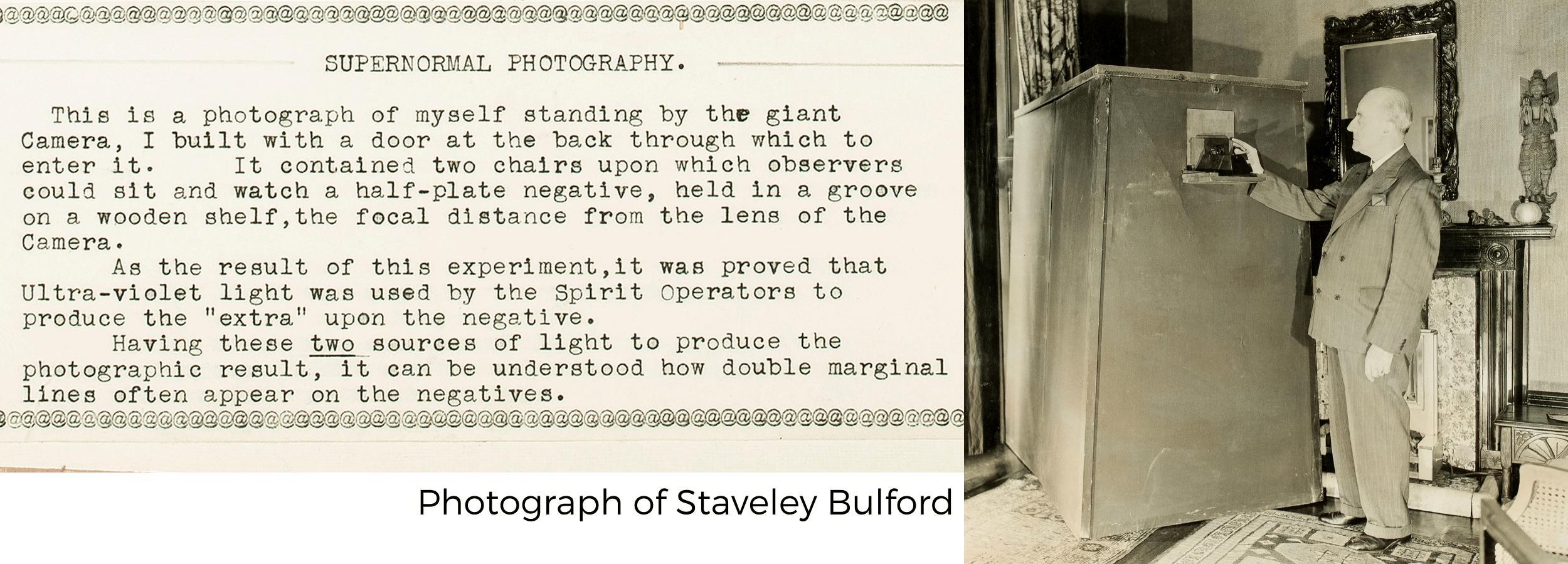

His spirit photographs were exhibited in 1923 at the Photographic Fair in Holland Park Hall and he travelled to spiritualist institutions and lectured on the subject. He continued to work on spirit photography, even using his carpentry skills to build a man-sized camera for experiments on ultra-violet light. He wrote two books, numerous articles, and tirelessly continued his quest for psychic truth. He remained a member of the magic circle until just before his death in 1958 at the age of 73.

On his death he bequeathed The College of Psychic Studies the collection of spirit photographs from his experiments of 1921. This means his legacy is enjoyed by new audiences and will continue to inform future generations of psychic investigators and spiritualists, as well as inspire modern day artists and photographers.

This article by College Curator & Archivist Vivienne Roberts featured in the College Journal Light in 2017.

Join our newsletter to receive more articles like this one, as well as updates on our courses, exhibitions and events.